The lockdown didn’t bring learning to a halt in Kashmir. It first happened after the abrogation of Article 370 on August 5, 2019. Schools shut; we were put under a communication blackout to prevent riots. The internet was blocked and so students couldn’t download study materials. Online education was not an option.

My name is Tanveer Ahmad Bhat. I am 49 years old and I have been a government school teacher for the last 17 years; this is the only job I know. I have taught in four schools across Bandipore’s Sumbal block – a primary school, a middle school and two high schools.

I teach mathematics to first generation learners – the children of farmers, agricultural labourers and mazdoors (daily wage workers). Some of my students don’t have money to buy a pencil or notebook.

Teaching in Kashmir is a challenge and more so in the last few years. We suffer ongoing curfews, closure of educational institutes and other workplaces. I sometimes feel I shouldn’t have become a teacher because we can’t fulfil our roles as teachers in Kashmir.

I like to teach through fun activities; I have played cricket and football with my students, taught card tricks, and given them little gifts like pens for memorising their tables. When I had to teach probability, I brought some pebbles, coloured balls, candies, and cards to use in the class. I put the coloured balls in the bag and asked students to pick one out to see the probability of a certain ball appearing again.

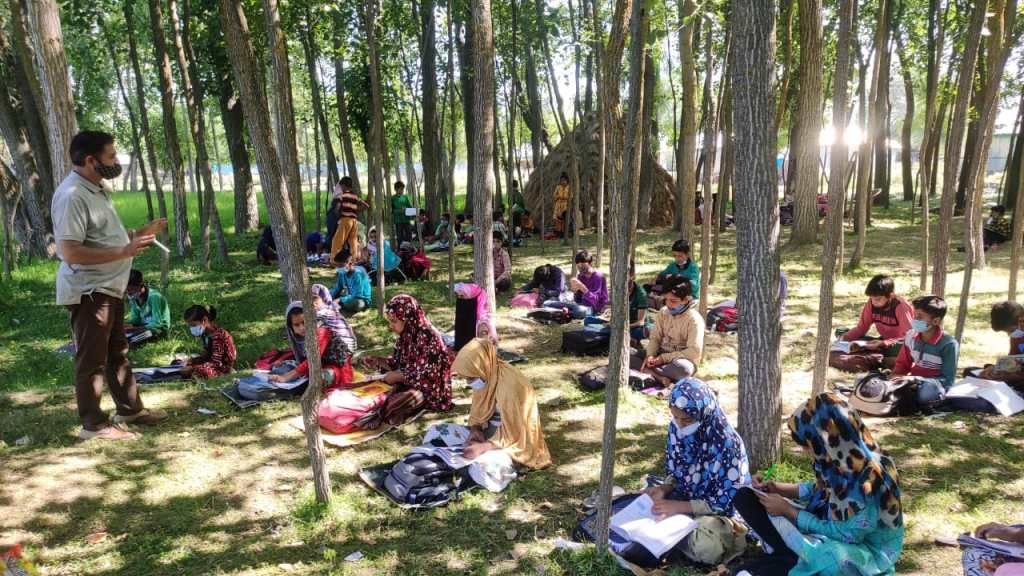

After Article 370 was scrapped in Kashmir and schools closed their doors, a few colleagues and I were determined to start teaching again, so we began to hold informal community classes in my village, Tirgam in Sumbal block; it has a population of 4,485 of which less than half are literate. We used a local playground where animals would be brought to graze.

We invited all teachers to join us and students could come at their convenience. But many were not punctual or would come just to meet their friends! Some were busy with household chores, and finally only 10-20 of my 60 students joined these community classes. Ongoing curfews added to our problems and made it difficult for us to hold these classes, but we continued engaging with our students till the winter vacations in November 2019.

The government allowed schools to reopen after the vacations – on February 24, 2020. I was eager to meet my students! I remember Zeya Raoof, a Class 9 student, excitedly telling me [when she arrived] that she felt like it was her first day of school. She had polished her shoes, washed and ironed her uniform three days before we reopened. We were all quite emotional when we entered Government High School, Tirgam that day. But less than a month later, in March 2020, schools shut again due to the outbreak of Covid -19.

Left: Zeya Raoof, 13, outside Government High School Tirgam. Her walk to school takes ten minutes by foot and she used to walk this route (right) with her best friend, before lockdown and other restrictions led to its temporary closure. Photos by Fouzia Fayaz

It was clear that no physical classes would be allowed, so I began online classes for my students in April 2020. It was very difficult to do online classes with 2G speed. Students could not see the screen properly, they could not hear our voices clearly and the videos we sent them used to buffer a lot.

My students began to lose interest – we had nearly 60 students in a class before the pandemic, but only nine or 10 of them were able to access a device and attend online classes. [In Kashmir, only 3.5 per cent rural households had a computer and 28.7 per cent had internet facilities, according to the 2018 National Sample Survey 75th Round. Additionally, the state was the worst affected by internet shutdowns in the country, according to a 2019 report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.]

Around November 2020, as the Covid-19 cases began to fall, we resumed community classes. The office of the Chief Educational Officer (CEO), Bandipora found these better for student attendance and asked us to continue doing them. Since I was teaching near the government school, I would carry the white board from school to the playground where I was teaching – a short ten-minute walk. We had to show photographic proof of our classes and were instructed to send the photos to the CEO’s office after each class. Through those photos, they kept an attendance record of the teachers who participated.

When the time for exams arrived, we had to conduct exams online. Six of my colleagues and I requested students who did not have phones to come to school, and we gave them our phones to do their exams.

Community classes are now on hold as cases rise with each wave.

As a government school teacher our duties go beyond teaching in school: during turmoil this teacher is a chowkidar; during surveys he is a patwari (government official), during elections he is a policeman and now during Covid-19 the teacher functions as a medical officer. All this is without any financial compensation. We can’t do the things we want to do, such as taking our students for educational tours to different places; we are limited to the four walls of the school.

This entire period has taken me away from my family – my wife Mehnaza Tanveer, 45, and sons Umar, 12 and Taha, 8. I spend a lot of time counselling my students who are anxious and mentally distressed by the closure of schools and the general conflict around. Sometimes, my counselling helps, but not always.

Sometimes I pay a student’s fees if they cannot afford it and I help them with basic things like notebooks, pencils etc. My wages were delayed during the pandemic and so I had to use my savings to live.

When I was growing up I lived in a joint family with my parents and my four siblings. I’m the youngest of the four. My late parents were both well educated – my mother was a government teacher at a middle school right here in Tirgam village and my father was a police inspector in Sumbal town, Bandipore. The literacy rate in Sumbal is only around 35 per cent, according to census 2011; I was fortunate to be raised in a family where education was a priority. When I was child, my mother used to take me to school with her. I looked up to my mother and wanted to be like her.

In February 2021, regular internet speeds were allowed in Kashmir, but now students have little to no interest in online classes. The ones that attend say they are tired, stressed, and suffer back and neck pain as they have to watch a screen during these classes. There are no extracurricular activities and they can’t play with their friends because of frequent lockdowns and curfews. They have become like prisoners, stuck in a cell.

Not just students, even teachers have mental health issues – we teach but we can’t see or meet our students. When delivering online classes, I feel like I am in some filmy world, acting before a camera, alone in a room.

Editor's note

Fouzia Fayaz has just completed Class 12 at the Government Higher Secondary School, Sumbal in Bandipore district of Kashmir. She was keen to report for PARI Education and worked for months on this piece - frequent internet breakdowns and suspension made it very hard for her to send photos and collect information. She says, “Reporting for this story taught me what journalism looks like – each statement needs to be supported with evidence. Through this story, I want people to hear the voices of teachers and children in conflict-ridden places like Kashmir. It was painful to learn that students are as distressed as I am because of the frequent shutdowns in the valley.”